Sibelius remastered or reimagined?

Classical music has a schizophrenic relationship with sound quality. On the one hand there is an obsessive preocuppation with hideously expensive 'acoustically perfect' concert halls. On the other hand recorded classical music has been chased down the rabbit hole of lo-fi by MP3s, streaming, ear buds, and mobile listening, and rarely - if ever - is sound quality mentioned in reviews of CDs. So it is not surprising but still disappointing that a major initiative by one of the largest classical labels to open the debate about recorded sound quality has passed unremarked, while classical's great and good continue their demands for yet another 'acoustically perfect' concert hall.

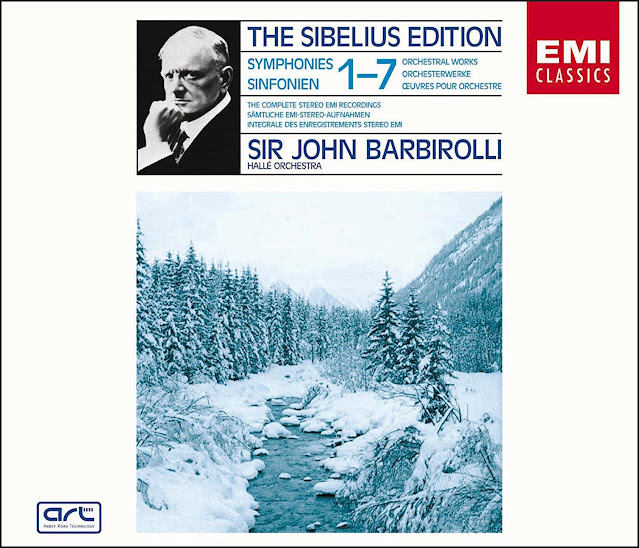

On the CD packaging Warner's Barbirolli Sibelius reissue is labelled as "Remastered in 192kHZ/24 bit from original tapes by Studio Art & Son, Annecy, 2020 (sic)." First let's dispense with the 192kHZ/24 bit hype. The compact disc Red Book standard sets the reproduction parameters as 44.1kHz and 16 bit. Anything higher than this makes good PR copy, but has no impact on CD sound quality. The superior resolution should however be noticeable on lossless FLAC file downloads, and the Sibelius recordings are available as 192kHZ/24 bit downloads. But why label the CD packaging in the same way?

My library includes the 2000 EMI Barbirolli Sibelius Edition which was remastered at Abbey Road. I was trained by the BBC as a radio studio manager, and I worked at EMI Classical Division in the late 1970s when the producers and engineers were still using the same technologies and techniques used on the Barbirolli recordings. I auditioned the Art & Son Studio remasters from CD using a studio quality replay system: see footnote for details of this. The following is my personal response to listening extensively to the remasters.

My appraisal above is a critical, but hopefully positive, review. Warner's decision to remaster the Sibelius and other recordings is commendable, and should have received more attention. It is also disappointing that reviews elsewhere have not drilled down into what the remastering involves. Most reviews have commented on the 'improved' sound. But improved compared with what? (The lack of perceptive reviews on sound quality probably reflects something I have posted about several times, the poor quality audio systems used by reviewers. )

* In my auditioning system CD replay is from a Denon DCD-1700NE CD/SACD player through QED Audio 40 cables into a Rotel RA-1592 integrated amplifier (200wpc). The amplifier signals travel along Audioquest Rocket 11 speaker cables in bi-wired configuration to Bowers & Wilkins Nautilus 803 speakers. Equipment is on a spiked Norstone Esse HiFi 4 rack with sorbothane footers. My listening room is purpose built and has very low ambient noise. All equipment is powered via a direct mains feed from the house's consumer board, via an unswitched mains socket with a high thermal stability fuse and custom constructed mains leads with professional quality IEC connectors.

Warner Classic's rerelease of Sir John Barbirolli's legendary Sibelius recordings are labelled as 'remastered'. But what is remastering? Mastering and remastering are two very different processes. When a recorded is mastered to CD very little is done to the sound other than marginally reducing the dynamic range to make it compatible with compact disc parameters. Mastering a CD effectively transfers the sound of the master tape with minimal modification. Remastering is very different, because it changes the original sound. Remastering originated in and is a standard practice in rock and popular recordings. Here is a definition: "Remastering music improves the quality of the original copy of a song or album. The process aims to remove flaws from the music, to provide a cleaner, sharper, and more refined listening experience in line with modern audio standards". In marketing-speak, remastering has the objective of making a recording more 'commercial'. To summarise, mastering a CD is effectively a 'flat' transfer of the original recording. While remastering seeks to 'improve' the original sound.

More schizophrenia becomes apparent here. Classical music is wedded to permanence. There are 'definitive' performances defined by interpretative dogma established over many years. And there are 'perfect' concert halls defined by acoustic conventions dating from the 19th century. Yet music is inherently impermanent. As soon as the last reverberations die away in a concert hall or recording studio the music is lost for ever, and cannot be recreated. In the recording studio the sound heard in the control room is not the same as in the studio. Because it has been modified by a complex of factors, the microphone set-up, the quality of the microphones, cabling, monitor speakers, the acoustics of the control room, etc etc. And the sound captured on the master tape is different again due to further electronic processing. While the sound heard by the listener at home is even more different. Because it depends on the CD/streaming transfer process, the quality of the domestic replay equipment, and the listening environment. So the concept of 'perfect' sound, other than that heard at the instant of performance is a misleading fallacy.

Art & Son Studio (the Warner labelling is incorrect) is a French enterprise. It started in 1999 transferring 78 discs, and in 2017 expanded to remastering digital recordings. As well as the Sibelius Edition the studio has remastered Furtwängler and Callas sets for Warner, and it also works for Universal Music. There is no information about Art & Son's remastering technique on their website, other than brief mentions of the digital workstations used - Cedar, Weiss, and Pyramix.

Auditioning the Barbirolli's Sibelius immediately highlighted that the sound has changed significantly; not only from the 2000 CD transfers, but also from the established balance of EMI recordings from that period. The sound has more presence: my 73 year old ears suffer from the usual age-related HF roll-off, but even to them the sound was noticeably brighter with more 'presence'. Frequencies of 4kHz to 6kHz are responsible for a recording's presence, and these are the frequencies inhabited by the harmonics of violins and the higher woodwinds. But the increased presence created by boosting mid-range frequencies favours certains instruments over others. This means that, on occasions, the lower pitch instruments, for instance timpani with fundamentals of around 70Hz to 300Hz, sound recessed. The increased presence was impressive; but after a time, for me, it became tiring.

Even more noticeable, and for me disturbing, was the widening of the stereo image. In the non-classical world widening the stereo image during remastering is standard practice. It makes recordings sound more impressive, particularly when auditioned binaurally - through headphones, ear buds etc. There is a wide range of plug-ins available to allow remastering studios to widen the stereo image. Again the widening of the stereo image on the Art & Son Studio was initially impressive. But, also again, it started to sound artificial, a perception emphasised by a 'hole in the middle' effect. Also there were some instances of image instability as the dominant frequencies shifted. The detrimental effect of manipulating the stereo image varies by CD and track. One of the worst examples is the remastered Barbirolli Cockaigne in the Elgar box. This sounds like one of those early stereo demonstration records with left and right sound and nothing in the middle.

My appraisal above is a critical, but hopefully positive, review. Warner's decision to remaster the Sibelius and other recordings is commendable, and should have received more attention. It is also disappointing that reviews elsewhere have not drilled down into what the remastering involves. Most reviews have commented on the 'improved' sound. But improved compared with what? (The lack of perceptive reviews on sound quality probably reflects something I have posted about several times, the poor quality audio systems used by reviewers. )

Art & Son Studio have reimagined rather than remastered Barbirolli's Sibelius. I do not dislike or reject these remastered recordings, and after auditioning the Barbirolli Sibelius set I bought the similarly remastered Barbirolli Elgar set. But I not throwing out my copies of previous less manipulated CD releases. It should be understood that what we are hearing is not closer to the master tapes, yet alone what happened in the studio. Art & Son Studio have taken the non-classical approach of taking the 'music to listener'. While the classical industry remains wedded, with little success in winning new audiences, of taking the listener to the music. Whether we like it or not, remastering has made Barbirolli's Sibelius more impressive, more immersive, and, as a result, more commercial. If that means more people are converted to classical music, it could be argued that is job done.

But there is a danger in this remastering exercise which needs to be highlighted. At Warner's behest Art & Son Studio have remastered the entire EMI Barbirolli catalogue and this has been released as the 'Barbirolli Edition'. Discs from this have appeared as smaller sets - e.g. an Elgar box - and individual releases. Given the culling of the classical catalogue and the unperceptive reviews elsewhere, it is quite likely that these remasters, which are an anonymous engineer's reimaging in an outsourced facility, will become the only versions available. This will be quite wrong. Virtually 'flat' transfers to CD and hi-res download copies of the master tapes must be kept available for posterity. This can easily be achieved by releasing all the material in hi-res files and CD/SACD discs.

Why SACD is overlooked as a hi-res disc format is a complete mystery, particularly in view of the resurgence in vinyl. SACD has a sampling rate of 2822.4 kHz and can contain 110 minutes of music without compression. The Philips/Sony license for SACD demands no additional royalty above the standard CD rate. So, other than the fixed cost of encoding software, an SACD disc should cost little or no more than a standard CD. An example of the constructive use of SACD is the Dutton Vocalion Epoch catalogue of SACD's which master celebrated archive recordings - such as Ormandy's Shostakovich 5 and 15, and Korngold's Die tote Stadt - to the SACD format. Decca are also hanging on in there with a SACD reissue of Solti's Ring, albeit at a scalping price.

There is another reason why these remasters are very important if flawed, and that reason has been totally overlooked elsewhere. Whether we like it or not, Warner know a thing or two about making music commercial to reach a wider audience. Which is what they have done with the Barbirolli recordings. Technology and audience expectations have changed dramatically in recent years, but the sound of classical music has not changed in recognition of this. As explained above, there is no such thing as a definitive classical sound, because sound is impermanent.

Art & Son Studio have reimagined and reshaped the classical sound to make it more palatable for a new audience, and they are to be commended for that. There is no definitive classical sound, just a set of long-standing rigid conventions and dogmas. Digital sound-shaping can change the classical sound to be more immersive and more appealing to new audiences. Yet such technology is rejected outright as heretical, despite the artform's obsessive search for a new classical audience. It is certain that the reviewers who have praised the sound of these remasters will have a hissing fit at the suggestion of concert hall sound being reshaped in line with changing audience conditioning and expectations.

It is vital that we do not lose access to the vision of the original producer and balance engineer. But classical music is impermanent and Warners have woken up to that . How long before the classical industry comes to the same conclusion?

Update - thought-provoking codicil to this post here

Comments

But the discs weren't selling enough (esp in light of downloads) and so they players stopped selling. What few I can find are either $5000, or only have a 2.0 channel, thus making the 5.1s (the reason I bought them) useless to me.

A format catch-22: you won't buy the discs if you don't have the player, but they don't sell the players so there's no point in pressing discs anymore.

I *want* my SACD player again, but either I get a used version of the one I have (with the risk that it dies in the same way because they're all getting equally old) or I lose my 5.1 because none of the affordable players support it (mostly because it got more expensive licensing patents for either the HDMI or the digital optical, though they should be expiring soon - my player only supported 5.1 through six RCA analog cables).

I completely agree with the poster.

All the Warner remastering carried by Art & Son have the same sound signature, regardless of the original recording facilities. To my 48 year old ears the lack vividness and seem a washed out picture of the original recording, aso fatiguing. I have auditioned FLAC hi-res files 24 bit/192 kHz. You can compare Klemperer Mahler Second Symphony mastered in 2011 by Abbey Road and the new April 2023 Art & Son remaster. I consider, also sonically, this recording one of the best available, the EMI SACD and Warner CD based on 2011 remasters are fantastic. The new 2023 remaster destroys the magic of the recording.