I design gardens with music

Zen has cast its influences on figures as different as John Cage and Toru Takemitsu. Takemitsu was working in a Western musical language, but, like a Japanese novel translated into English, his compositions contain something different. Takemitsu said he only uttered 80 per cent of any idea, in what could be construed as powerful understatement; the rest is silence, the pregnancy of the unsaid, ma. Ma, a profoundly important concept in Japanese culture, is the silent understanding when friends are together, or when one is contemplating nature or art - when meaning is intense but nothing is expressed.

That is Jonathan Harvey writing in his book In Quest of Spirit: Thoughts on Music. In Japan the silent contemplation of nature reaches its apogee in the art of Zen gardens. Buddhism came to Japan from China via Korea in the 7th century, and the first known garden designed on Buddhist principles was created in 618 by a Korean immigrant Roji-no-Takumi. In this pioneering garden Mount Semeru (the mountain at the centre of the Buddhist universe supporting the heavens) was represented by a mound linked to a viewing point by a connecting bridge, and this established the principle of the Zen garden as a visual haiku,. Over the subsequent centuries the art of the Zen garden has been refined, but their function as visual haikus remains their raison d'être. Much of Japan is mountainous, so 94% of the 126 million population is crowded into urban areas where space is at a premium, and the Zen garden allows nature and spiritual symbolism to be brought into urban areas where space is at a premium.

As Jonathan Harvey recounts, Zen was a major influence on Toru Takemitsu. Zen gardens were a particular influence on the composer, and he once explained that 'I design gardens with music'. The Saiho-ji Temple in Kyoto designed by the 14th century Zen priest Muso Soseki inspired Takemitsu's Dream/Window for orchestra. Another work that reflects the composer's preoccupation with Zen gardens is his Spirit Garden; this uses a twelve note row to generate three chords each of four notes, with these sound 'objects' being heard in a sonic garden from different perspectives. This preoccupation is reflected in the numerous botanical references in the titles of Takemitsu's music, including In an Autumn Garden, A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden, Tree Line, Garden Rain and Music of Trees.

William Glock's discrimination against certain composers in the 1960s and early 1970s is a cause célèbre. The current more nuanced neglect of other composers receives insufficient attention. Takemitsu is an important figure in late-20th century music whose oeuvre is progressive yet accessible. Despite this the last time his music was played at the BBC Proms was in 2010 and his works have only featured in thirteen Proms. It is a pithy comment on the priorities within classical music that in the last six years Paddington Bear has made more appearances at the Proms than Toru Takemtisu's music. For those who have not experienced Takemitsu's exquisite sonic gardens, the low-priced 2 CD Brilliant Classics overview of his music - which includes Spirit Garden - goes where the Proms planners fear to go.

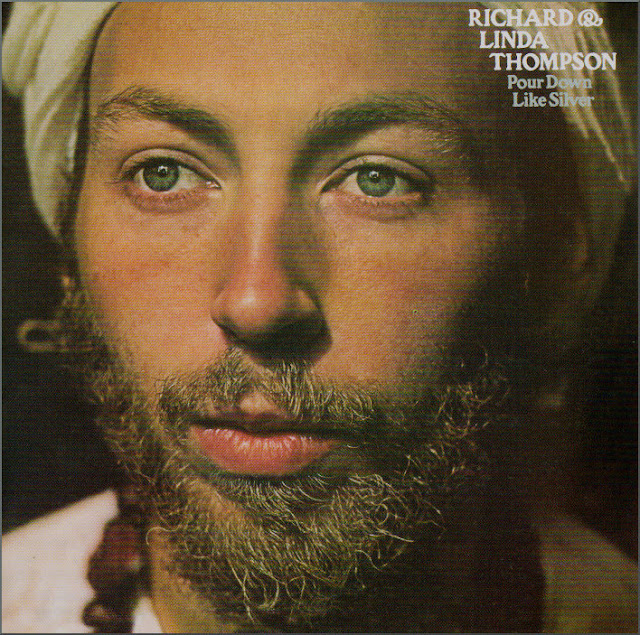

Buddhist author and teacher Stephen Batchelor explains that "A Zen garden can say as much about what the Buddha taught as the most erudite treatise on emptiness". When I first visited Japan in the 1980s I spent time in the famous Zen garden at Ryoan-Ji temple in Kyoto. Since then it become a tradition to create a Zen garden at each of our homes. The accompanying photos show the garden designed and built by my wife and me in our current home in Norfolk. This visual haiku represents the Buddha striving to reach enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya. The barriers to enlightenment are represented by the cluster of rocks seen in the photo above, and enlightenment is depicted by the yukimi-gata (snow-viewing) lantern seen below. Contemplating our spirit garden helps me to understand what Toru Takemitsu meant when he wrote:

...I wish to search out that single sound which is itself so strong that it confronts silence. It is then that my own personal insignificance will cease to trouble me.

Sources include:

In Quest of Spirit: Thoughts on Music by Jonathan Harvey

The Art of Zen Gardens by A.K. Davidson

A Japanese Touch for Your Garden by Kiyoshi Seiko, Masanobu Kudō & David. H. Engel

Confession of a Buddhist Atheist by Stephen Batchelor

Also on Facebook and Twitter. Any copyrighted material is included as "fair use" for critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).

Comments