Eat the meal not the menu

My recent reading has included Charlie Harmon's On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein. This deliciously unexpurgated account of his years as Bernstein's personal assistant in the 1980s resonated with me as I swam in similar murky waters at around the same time.

Sometimes I glance at the online reviews of books and CDs; not because I trust the dubious wisdom of online crowds, but because online reviews provide a useful guide to the cultural zeitgeist. An Amazon reviewer criticises the book because a "little too much of the book is about Harmon". Let's leave aside that there are already more than enough books about Lennie. The online reviewer misses the vitally important point that what really matters is the interaction between the music/musician/composer and those around him - personal assistants, audience, et al.

Benjamin Britten famously identified this in his 'holy triangle of composer, performer, listener'. His identification of the non-locality of music was subsequently confirmed by the discovery of quantum entanglement by sub-atomic physicists. And Britten's ratification of the non-locality of music has been further confirmed by the technology-driven trend of mobile listening.

The mistake of trying to separate the music from the listener is the same as eating the menu and not the meal. And that error is not confined to an Amazon reviewer: it is perpetuated by the whole of the classical industry. New listeners are told to eat the same set menu of Shostakovich and Mahler punctuated by amuse bouches of virtue signalling trifles. (Does BBC Radio 3 really have nothing else to programme than increasingly lacklustre performances of Mahler 1, followed the next day by, yes you guessed it, another Mahler symphony?)

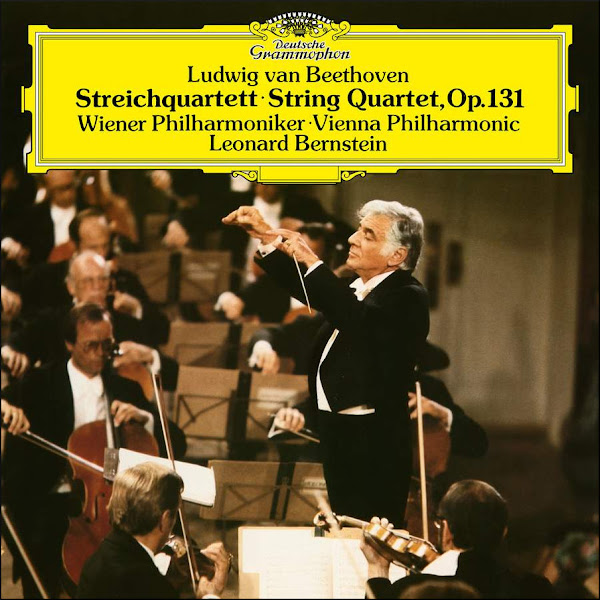

Missing are what the Japanese calligrapher Sabro Hasegawa called 'controlled accidents' This is the shock of chance entanglement I felt many years ago when digging deep into the classical a la carte menu and discovering, for instance, the visceral power of Bernstein's recording of the orchestral version of Beethoven's op. 131 Quartet. This absence of fortuitous controlled accidents probably explains why classical music is struggling to retain its current audience, yet alone win new converts..

Comments