Classical music's mighty and single cosmic rhythm

On the cover of the invaluable anthology The Essential Titus Burckhardt is an endorsement by the composer John Tavener which describes how the philosopher's prose “breathes like some mighty and single cosmic rhythm, which Burckhardt understood so well”. Titus Burckhardt was a member of the sophia perennis (perennial wisdom) school of philosophy, which focuses on the timeless Truth and practices that are shared by the great knowledge traditions, and deplores the rise of materialistic and secular humanism.

The perennialist view that "a supreme power of discrimination can only go hand in hand with the highest knowledge, and that is given to a few, not to the generality" can be interpreted as elitist, and, indeed, some connected with the perennialist school - notably the Italian philosopher and esotericist Julius Evolva - had disturbing fascist sympathies. But before dismissing perennialism as a reactionary anachronism it is worth remembering that many of the most influential figures in modern music are linked some way to the mighty and single cosmic rhythm. Among those with links to the great knowledge traditions are Olivier Messiaen, Arvo Pärt, John Cage, Philip Glass, Henryk Górecki, Sofia Gubaidulina, Jonathan Harvey, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and, of course, John Tavener - the premiere of the latter's perennialist influenced Requiem in Liverpool Cathedral provides my header image. All these composers are noted for their contributions to contemporary music, but there is another less-celebrated musician who was an authority on both early music and perennialism. Marco Pallis, whose writings about Buddhism contributed to the Western resurgence of interest in that great tradition, was a gifted viol player and composer who taught at the Royal Academy of Music and made an important contribution to the early music revival.

Marco Pallis was born in Liverpool in 1895 to Greek Orthodox parents. After attending Liverpool University - where he toyed with Roman Catholicism - and then being wounded in the First World War, he went on to pursue his two great passions, mountaineering and music. He studied with Arnold Dolmetsch, who not only transmitted his passion for early music but also introduced Pallis to the writings of René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy and other perennialists. From his own funds Pallis financed a much-needed expansion of Dolmetsch's workshop in Haslemere where viols and replicas of early keyboard instruments were produced. In a fascinating pre-echo of that other great musician and rearranger of the geometry of heaven Jordi Savall, Marco Pallis’ instrument was the viola da gamba, and in the 1930s he formed the pioneering English Consort of Viols. For a while Pallis was honorary secretary of the Dolmetsch Foundation which supported the renaissance of early music in authentic performances, and, as part of his worldview, brought the Sinhalese musicians Nelun and Surya Sena for a performance at Haslemere.

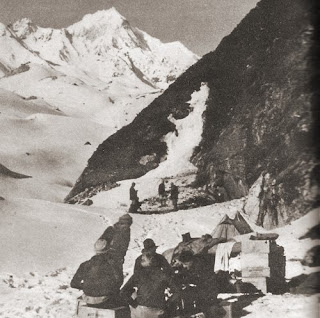

In the photo above Pallis is seen with his fellow mountianeers on the Zemlu Glacier in the Eastern Himalayas. His viol accompanied him on these arduous expeditions; here, in his own words, is an account of mobile music making in the pre-iPod year of 1933.

Chini is an important post on the Hindustan-Tiber road, which connects Simla with the trade-mart of Gartok. All along it bungalows have been erected at convenient intervals by the Public Works Department; we were glad to use them, for they are comfortable and invariably placed with an excellent eye for a commanding view. Staying in these houses we gained additional enjoyment from being able to have regular chamber music every evening, playing on two viols, treble and alto, which had accompanied us so far without our having found an opportunity to use them. String music that sounds complete in two parts, needing no accompaniment, is not easy to find. Our great stand-by was the book of two-part Inventions by Bach, which though composed for the keyboard, transcribe excellently for viols. We also had a set of fantasies in two parts by Thomas Morley, which are authentic viol music. Finally we arranged a number of sixteenth-century English and Spanish tunes in such a way that, by the generous use of double stops, they sounded like a full quartet. It often happened that, unperceived by us, a little group of porters would gather quietly round us and listen intently. They formed a perfect audience, unobtrusive yet seeming to possess the true faculty for listening. Playing our national music to these foreign but sympathetic listeners, we could not help recalling the words of Thomas Mace, a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, who wrote a book in the middle of the seventeenth century entitled Musik’s Monument. In the last chapter he speculates on the method of communication that will be used in heaven by members of the diverse nationalities there assembled. There must, so he argues, be a common language intelligible to all mankind, and the only known language that fulfils that condition is music.Many of Marco Pallis' fellow perennialists followed the esoteric route from Catholicism to Sufism, but he found his spiritual destination in Buddhism and became an acknowledged authority on the Tibetan tradition. His best selling book Peaks and Lamas - which Philip Glass acknowledges as an influence - was the product of several trips to Tibet in the 1930s. Pallis converted to Buddhism in 1936, and after the Second World War returned to Tibet, where he studied with lamas and took the name Thubden Tendzin after being ordained. Following his visit to Tibet, Pallis lived in Kalimpong in West Bengal where a harpsichord graced his home.

After the Chinese invasion of Tibet, Pallis returned to live in London where he championed the Tibetan cause. At the same time he established his reputation as a musician by teaching viol at the Royal Academy of Music and reformed the English Consort of Viols which went on to make several groundbreaking records - see above. Pallis had a long correspondence with the Trappist monk and advocate of inter-religious dialogue Thomas Merton, and when the English Consort of Viols toured America in 1964 he visited Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemane in Kentucky. The invaluable compendium Merton & Sufism: The Untold Story has a chapter devoted to Merton, Marco Pallis and the traditionalists. Merton's published Asian journal, which was written in 1968 during the trip which ended with the monk's tragic death in Bangkok, contains no less than seventeen references to Pallis, and Merton was planning to visit him in Wales on the return leg of the fateful trip.

Marco Pallis was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, and in 1989 composed a String Quartet in F# for the Salomon Quartet which was performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London. To my knowledge the quartet has not been recorded, but the score remains in print and is described in the publisher’s catalogue as follows - “this hauntingly beautiful piece, with echoes of the style of Henry Purcell, lies within the range of an advanced student quartet”. When Pallis died aged ninety-four in June 1989 he was, tantalisingly, working on an opera about the life of the Tibetan saint Milarepa. At which point the wheel of life brings this post full circle. Because the Temple of the Thousand Buddhas at La Boulaye in France was inspired by the teaching of Milarepa, and, after visiting the temple in 2009, I featured it in a post about the string quartets of Jonathan Harvey, one of the composers who was linked at the start of this path to the perennialists.

Sources include:

~ Peaks and Lamas by Marco Pallis

~ The Early Music Revival by Harry Haskell

~ Merton & Sufism: the untold story edited by Rob Baker and Gray Henry

~ Dolmetsch: the man and his work by Margaret Campbell

~ Marco Pallis' Life and Work - World Wisdom online biography

~ The Essential Titus Burckhardt edited by William Stoddart

~ The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton - various editors

~ The Perennial Philosophy by Aldous Huxley

No review samples were used in the preparation of this post. Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Also on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments

Which does confirm the point I made yesterday that daring to be different has its merits.