Cleaning the ears of the musically educated

It was, as I remember, through Jean [Erdman} - who is to dancing what Vivaldi was to music - that we met the other member of the party, composer John Cage, who had then become interested in the relationship of music to Zen and was beginning to explore the melodies of silence. My principal tie with John was that we had the same kind of humour, for he would simply bubble with laughter whenever describing his latest plans for musical outrage, such as a very formal piano recital in full evening dress, complete with an assistant to turn the pages, in which, however, the score consisted entirely of rests.

The joke wasn't merely that he was getting away with murder in the hopelessly deranged world of avant-garde music, so as to constitute the master charlatan of all, but that beyond all this and to make matters still funnier, he had also discovered and wanted to share the meditation process of listening to silence. This is simply to close your eyes and allow your ears to resonate with whatever sounds may be happening spontaneously, making no attempt to name or identify them, just as when one listens to formal music. After a while one hears the sounds emerging, without cause or origin, from the emptiness of silence, and so becomes witness to the beginning of the universe.

John slept that night on a divan in the living room, where we kept a hamster in a cage furnished with a vicous wheel, or bhavachakra, wherein the benighted creature could run forever without getting anywhere. This particular wheel squeaked abonimably as the hamster ran, so I told John to put the cage out in the passage if it bothered him. "Oh, not at all!" he said. "It's the most fascinating sound, and I shall use it as a lullaby."

What may not be generally understood about John is that he is an extremely accomplished musician who has, however, realized that we do not know how to listen. Conventional music, as well as conventional speech, have given us prejudiced ears, so that we treat all utterances which do not follow their rules as static, or insignificant noise. There was a time when painters, and people in general, saw landscape as visual static - mere background. John is calling our attention to sonic landscape, or soundscape, which simultaneously involves a project for cleaning the ears of the musically educated public.

As painters once framed "mere" landscape, John is using the ritual of the concert hall to frame silence and spontaneous sound, which we shall in due course find as beautiful as sky, hills, and forests. Imagine, then, the sonic equivalent of those places in national parks usually called Inspiration Point where tourists from Kansas exclaim at the view, "Oh, it's just like a picture!" Buddhahood is the state in which all sensory input is viewed in this way.

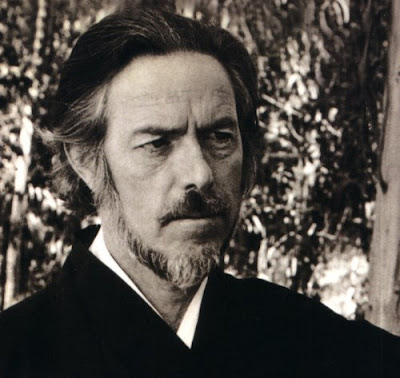

Priceless 'John Cage for dummies' from Alan Watts' autobiography, which has recently been republished by New World Library, Novato, California. Alan Watts, who is seen in my header photo, was born in England in 1915. He met the Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki at an early age, and moved to America where he became an Episcopal minister.

After leaving the church Alan Watts wrote more than twenty books on Zen Buddhism, and his teachings were one of the triggers for "beat Zen" in the late 1950s which saw expression in Jack Kerouac's novel Dharma Bums, Franz Kline's black and white abstractions and John Cage's compositions. In the 1960s Watts was considered by many to be a counterculture 'guru', and his circle included Timothy Leary, Aldous Huxley and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass). Watts was also an early environmentalist, and he died at his mountain retreat near Muir Woods, California in 1973.

Buddhism has been an important influence on many other modern composers including Philip Glass and Lou Harrison in the States, and Edmund Rubbra, John Palmer and Jonathan Harvey in England. In My Own Way is the compelling story of one man's pursuit of the Buddhist way, and the impact that his teachings had on many other important twentieth-century figures. Highly recommended, together with the Asian Journals of the Catholic mystic Thomas Merton.

* I am sure my readers' ears do not need cleaning, but this Sunday (Feb 10) you can hear John Cage's Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra on my Future Radio programme at 5.00pm on Feb 10 and 12.50am Feb 11 framed by Canzoni by the 17th century Italian composer Girolamo Frescobaldi.

Now read about Zen and the art of new music.

Alan Watts website here. Listen on Future Radio at 5.00pm UK time this Sunday, Feb 10 and 1.00am Monday Feb 11 real time here (convert to local time zones here). Windows Media Player doesn't like the audio stream very much and takes ages to buffer. WinAmp or iTunes handle it best. Unfortunately the royalty license doesn't permit on-demand replay, so you have to listen in real time. If you are in the Norwich, UK area tune to 96.9FM. Report broken links, missing images and errors to - overgrownpath at hotmail dot co dot uk

Comments

You can find a number of his recorded lectures and videos on the Internet Archive

In many ways, I think what he said still applies today. Maybe even more so.

Thanks for reminding me.