The real 'Piano Man'

"Here then…are some of the harsh facts behind the words ‘severe mental illness’ and ‘serious nervous breakdown’ which the press has been using about me so often lately. Not that I am complaining about the press! – I was thrilled by the sympathetic and wide spread media interest that came my way both before and after my return to the….concert stage" - these words were written by the real ‘Piano Man’ John Ogdon in 1981.

"Here then…are some of the harsh facts behind the words ‘severe mental illness’ and ‘serious nervous breakdown’ which the press has been using about me so often lately. Not that I am complaining about the press! – I was thrilled by the sympathetic and wide spread media interest that came my way both before and after my return to the….concert stage" - these words were written by the real ‘Piano Man’ John Ogdon in 1981.Ogdon (above) was thrust into the limelight in 1962 when he was joint winner, with his friend Vladimir Ashkenazy, of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Competition. He wowed the Moscow audiences with his performances of Rachmaninov, Balakirev and Scriabin, as well as the Tchaikovsky 1st Piano Concerto which became his signature piece.

Although Ogdon is mainly remembered today for his stunning interpretations of the Russian romantic repertoire he was also a ceaseless performer of modern music. He studied in Manchester at the same time as Peter Maxwell Davies, who wrote his Opus 1 Sonata for Trumpet for Ogdon and Elgar Howarth, and his Opus 2 Five Pieces for Piano for him in 1956. Ogdon became part of what is now known as the ‘Manchester School’ together with Harrison Birtwistle and Alexander Goehr.

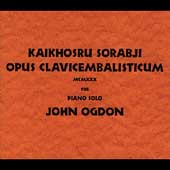

John Ogdon’s appetite for new music was insatiable. He gave the first performance in 50 years of Kaikhosru Sorabji’s (1892-1988) four hour epic, Opus Clavicembalisticum, and then offered to repeat the piece as an encore! He went on to record the Sorabji, a recording that is still in the catalogue. (Despite his exotic name Sorabji was born in Essex, England!) Among the other contemporary composers that Ogdon championed and played were Ronald Stevenson, Christopher Headington, David Blake, Malcolm Williamson (who dedicated his Sonata for Two Pianos to him), the American Richard Yardumian, and his long-time friend and supporter Gerard Schurmann.

Somewhat surprisingly Ogdon admired the work of Cornish tonal composer George Lloyd whose piano concerto ‘Scapegoat’ was dedicated to him, and which was described by Ogdon as ‘almost a masterpiece’. He was also a fan of jazz, and as Artistic Director of the Cardiff Festival of Twentieth Century Music he programmed Gershwin and Ellington alongside Boulez and Szymanowski. He was one of the first pianists to tackle Messiaen’s Vingt regards, was a ceaseless champion of Alkan’s oeuvre, and was responsible almost single-handedly for the rehabilitation of Busoni’s Piano Concerto.

As if this wasn’t enough Ogdon was also a prolific composer. His Theme and Variations was written for none other than Vladimir Ashkenazy. He wrote solo sonatas for piano, violin, flute and cello, a string quartet, and a quintet for brass, and left an uncompleted symphony inspired by the writings of Hermann Melville. His most ambitious work was a Piano Concerto, of which he made a long-deleted recording for EMI.

As if this wasn’t enough Ogdon was also a prolific composer. His Theme and Variations was written for none other than Vladimir Ashkenazy. He wrote solo sonatas for piano, violin, flute and cello, a string quartet, and a quintet for brass, and left an uncompleted symphony inspired by the writings of Hermann Melville. His most ambitious work was a Piano Concerto, of which he made a long-deleted recording for EMI.But if Ogdon’s creativity blazed across the heavens like a meteor, sadly his mental health spluttered like a dysfunctional firework. He made three attempts at suicide, one was by cutting his own throat. There were long stays in the specialist psychiatric Maudsley Hospital in London, interspersed by long periods of depression. There was electroshock therapy and lithium treatment. But ironically Ogdon died on August 1st 1989, aged 52, of natural causes connected with undiagnosed diabetes.

John Ogdon’s wife, the pianist Brenda Lucas Ogdon, supported him through illness. She has continued to champion his work long after it dropped out of fashion, and runs the John Ogdon Foundation. In 1981, eight years before his untimely death, she wrote a biography titled Virtuoso. It is John Ogdon’s own words from the Foreword that I used at the start of this article. And I will conclude by quoting his wife's Afterword which is as relevant to the Piano Man in 2005 as it was to John Ogdon twenty-four years ago.

"I have been amazed how many people have confided in me, as if to a comrade in arms, that a spouse, a relative, or a friend – even, on occasion, they themselves – had undergone a comparable ordeal (if not so extreme a one). But why have they hidden that experience from the world? Why, when most of them admit to having been deplorably ignorant when they were first forced to cope, do they not give advice and warnings to others? What is it that they are ashamed of.......?"

For a related story take An Overgrown Path to Music and Alzheimer's.

There is a superb sketch of John Ogdon by Milein Cosman on the National Portrait Gallery web site. Unfortunately this gallery charges for the use of their images on web sites so I haven't linked to it. As the sketch is not currently on public view at the Gallery this seems rather self-defeating. It is worth following the link as there are lovely sketches of other musicians including the Amadeus Quartet there. I fully sympathise with the drive for intellectual property protection. But in this case shouldn't the Gallery be taking the risk of exposing the works under their stewardship to public view?

Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Report broken links, missing images and other errors to - overgrownpath at hotmail dot co dot uk

Comments

Having just watched -- with my spouse this past Sunday night -- the generally acceptable and strong Hollywood treatment of New York Times writer Sylvia Nasar's story of American mathematics and economics Nobel laureate John Nash, "A Beatiful Mind", I can only say that this short "on an overgrown path" posting affected me just as deeply. (I had read the Nasar book years before seeing the movie.) I will trust that Mr Ogdon's sketches for his Melville Symphony are in safe and responsible hands.

Is it really that good? How does it compare to the best?

My view is that Ogdon was an extraordinarily powerful, and moving, player. But there are many other pianists whose playing was closer to the letter of the composer's intentions, but not necessarily closer to the heart of the composer.

That's my view. Here are some random critics writing about his recorded interpretations of Rachmaninov....

these recordings... show Ogdon in the repertory he loved best.... cutting through the torrents of notes to find the structural core... the sovereign command of the playing is never in doubt."

[Andrew Clements, The Guardian 23/8/02]

"... a three-disc set that testifies to Ogdon's remarkable affinity with Rachmaninov's musical idiom... He is in commanding form."

[Geoffrey Norris, The Daily Telegraph 31/8/02]

" what shines through is a breathtaking mastery of the idiom and compelling musical imagination to keep you ont the edge of your seat. Ogdon exalts in the turbulent Etudes Tableaux as never before. An unmissable set.'

[Julian Haylock, Classic FM Magazine, October 02. Rated by Classic FM Magazine as Best Buy Instrumental CD October 2002 ]

"... these are deeply satisfying performances, poetic as well as virtuosic, especially in the Preludes where the changes of mood are superbly captured and manipulated.... he is in dazzling form... Both the sonatas are grandly performed .... No student of pianism will want to be without these discs."

[Michale Kennedy, The Sunday Telegraph 15/09/02]

Hope that helps.

George Lloyd was a post-Vaughan Williams phase I went through. Fine tonal workmanship (a bit like a Cornish Hovhaness). But I have to confess I can't really recall a note, which is why I was somewhat surprised at Ogdon's advocacy. (He is not to be confused with the Jonathan Lloyd, an altogether more sinewy contemporary British composer whose 4th Symphony recorded on NMC I recommend to you.

For me the real 'nugget' within Ogdon's advocacy is the Frenchman Charles-Valentin Alkan who was admired as a composer by Liszt and Busoni. He does have a justified reputation for bombast. But some of his writing is exquisite. I do recommend his last cycle of miniatures, the appropriately named Esquisses Op. 63 (fine recording by the wonderful Steven Osborne on Hyperion), and his 25 Preludes, Op. 1 (which again played by Osborne come coupled with the Shostakovich Preludes on Decca).

So much wonderful music, and so much little known...

I know. I know.... I actually own a second-hand copy of, and listened to years ago, the George Lloyd CD with the Scapegoat Piano Concerto (and also perhaps one other GL Symphony recording)but,like you, I can't much recall it. It is even hazier in my mind than the Peter Dickinson piano and organ concertos, which you must recall since I think that they were (first) on EMI. (I have a much stronger knowledge of most of Birtwistle's works, though I don't yet own Theseus Games, as the DGG is not yet available in the States, and I am still saving for the score. And the last CDs on my player, two weeks ago, were several of the Maxwell-Davies Symphonies, as well as Alexander Goehr's The Death of Moses, which I am growing to like and admire after having been less impressed after a single listen some years back. It certainly pays to revisit works.)

Thanks for the Jonathan Lloyd recommendation. While I have most of the all but most recent NMC recordings, I don't have his Fourth Symphony, nor can I recall hearing any of his music. I must do so. I must also give some of the other more recent NMC CDs of British orchestral works (by Butler, Payne, Finnissy and several others -- mostly with the BBC Symphony, I think) another look and listen. I'm glad to have the Jonathan Lloyd recommendation.

And I must also find a late summer perfect moment to relisten to Havergal Brian's Gothic Symphony, my second-hand copy of which I got back from a friend from Indian who absolutely loved it -- his wife borrowed from me my copy of Philip Glass's Symphony #5 - his oratorio/symphony. (It won't be this weekend, as we are finally off to the mountains.)

To repair that omission here it is.