Have all the really great musicians come and gone?

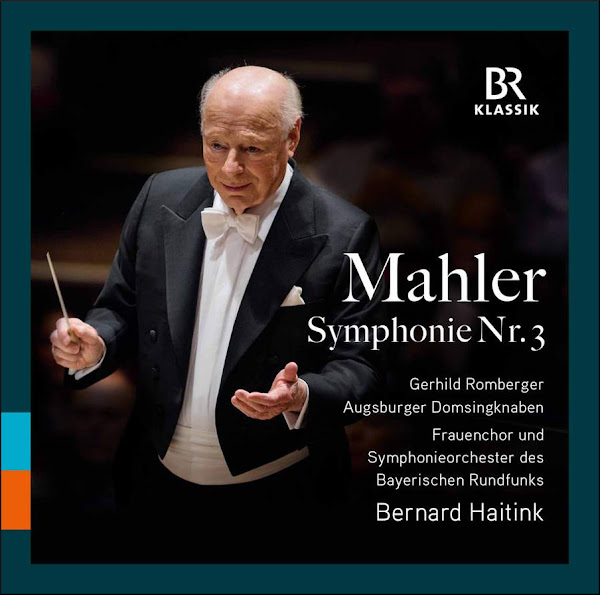

Bernard Haitink's 2016 recording of Mahler's Third Symphony is arguably the greatest interpretation of that towering work committed to record. It is also one of the last testaments from a conductor who together with Georg Solti, Herbert von Karajan, Sir Adrian Boult, Colin Davis and others defined a golden age of classical music. In response to my post 'Classical music's biggest problem is that no one cares' reader David has posted a comment that starts by asking "...have all the really great performances, recordings indeed all the greatest musicians come and gone?" He then goes on to observe that "I haven't heard anything in the last twenty or more years that compares with previous generations".

The classical industry has spent much time agonising over its failed attempts to reach a new audience. But an even bigger problem has received little attention. Not only is the new young audience remaining elusive, but the older long-established audience - including me and I suspect David - is becoming increasing disillusioned with the current classical culture. Over the last 50 years I have worked in the classical industry and spent an awful lot of money on concert tickets and records. But now, like David, I find my attention - and importantly my expenditure - wandering further and further away from mainstream classical music, because the current offerings on disc and in the concert hall are so bland and unappealing. Today we are expected to accept Mahler interpreted with added celebrity, added click bait, and added virtue signalling as a substitute for Mahler interpreted with blazing conviction and unsurpassed musicality.

David's observation that technology has overtaken culture demands serious consideration when the beleaguered classical music industry continues to bet its future on streaming. Some will interpret David's views and my endorsement of them as reactionary. So I will remind readers that I was in the vanguard of advocating equality in classical music. But I have watched with despair as female musicians and musicians of colour have been turned indiscriminately into marketable brands, regardless of merit. David's views are not reactionary because he laments the demise of fringe influences on contemporary classical music. Pierre Boulez emerged from the classical fringe to become a powerful agent of change. His tenure as principal conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra between 1971 and 1975 not only coincided with, but was also a fundamental influence on classical's golden age.

Hearing Boulez perform his own compositions at the Roundhouse during that era was part of my musical education, as were Sir Adrian Boult's valedictory Proms performances of the Elgar symphonies. This despite Boulez and Elgar's music being as different as day and night. David's point is that to have light you also need darkness. Playlists, mixtapes, Classic FM, and an obsession with social media approval has bleached out that vital creative tension. Here is his comment:

Another theme is have all the really great performances, recordings indeed all the greatest musicians come and gone? I haven't heard anything in the last twenty or more years that compares with previous generations. A similar phenomenon has been observed in the field of pop music. One could put this down to, as Fischer-Dieskau diagnosed it, technology overtaking culture. One finds technological advances have taken the place of cultural development across all forms of media. There is more available, and a lot of it instantly, but nothing of comparable quality is being produced or created now.

One might also see it as the decline of the classical tradition or even the West in general. The collapse of Christendom (Muggeridge?)... as a lot of classical music is either directly or indirectly underpinned by the Church and its values. I find very little to get excited about now in the classical music scene. Certainly the (over) promotion of female composers (unjustly?) hidden in history hasn't yielded anything groundbreaking despite endless propagandising by the BBC to the point Robert Schumann cannot be mentioned on Radio 3 without playing a tedious excerpt from one of Clara Schumann's compositions or the time given to the sentimental musings of Florence Price. It is all very well inserting minority interest politics into culture but it does make for any great art or revelations in the same way special interest groups have ruined political debate and commitment.

Agit prop inspired fringe theatre, music and culture have fallen by the wayside. Hence a soul-less younger generation without ideals. Perhaps cross over concerts/projects of the sort mounted by Jordi Savall (I liked his Tears of Lisbon album which combine modern Fado with Gregorian chant very much and reminded me of Marcello Mastrioanni's last movie Voyage to the Beginning of the World set in Portugal) and in the album [Ibn Battuta] featured at the article 'Classical music's biggest problem is that no one cares'.

Comments

The demise of Christendom thesis might invite some over-eager reactions. I personally think that Christendom has been too varied to make sense as an explanation for a decline in the state of classical music. Zwingli & Bullinger banned music from churches in Geneva but it's not like music was banned everywhere. The scholar Charles Garside Jr went so far as to argue that the Zwingli/Bullinger legacy had the effect, by banning music from churches, of catalyzing music as a creative discipline separated into a functionally secular realm. Germans, on the other hand, promulgated what is broadly identifiable as German art-religion in the Wagnerian and post-Wagnerian mold.

What if the "crisis" in classical music is that the credibility of Romantic art-religion in a Germanic cast has reached a low point? A side effect of a demise in Romantic sounds might be that someone like Price isn't going to move past her idiom compared to Ellington or even Scott Joplin. Joplin's influence on American popular music is far more palpable to me.

Romantic era art-religious ideologies are relatively recent inventions and J. S. Bach and Haydn didn't need them to write amazing music.

I think there's a point in favor of arguing that when the art-religion of Wagner emerged and WASPS embraced it there were racist elements to it but when I see there's a Church of Coltrane it's possible to have a kind of post-Wagnerian art-religion for jazz and rock, too, a kind of residue of Romantic art-religious ideologies that crop up for popular as well as classical styles.

My own theory has been that in the last two centuries "highbrow" and "lowbrow" musical styles and their journalistic and academic partisans have entrenched the scholastically and journalistically constructed barriers. Laurence Dreyfus said in his book on Bach and forms of invention that 19th century theory and pedagogy reduced analysis to form-as-genre in a way that misrepresents how fluid boundaries between forms and genres often have been.

I don't know that 1970s rock/jazz fusion is going to come back but I think working across all the musical genre boundaries to sustain a synergistic theoretical and practical cross-genre collaboration among musicians and composers could help people across the pop/classical divides.

But music journalism and scholarship too often seems set on antagonizing the scene rather than exploring possible convergences.