Classical Uber has arrived and this is the result

Last night I was at Snape Maltings for the first day of the William Alwyn Festival. The centrepiece of the evening concert was a powerful and persuasive performance of Alwyn's Fourth Symphony with John Gibbons conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Complementing the little-known symphony were Glinka's Ruslan and Ludmilla Overture, Borodin's In the Steppes of Central Asia and Elgar's evergreen Cello Concerto with Jamie Walton as soloist. Although William Alwyn was a Suffolk resident his music did not find favour with Benjamin Britten. However and despite this, the blessed venue that Britten created allowed John Gibbons and his forces to remind us - if any reminder was needed - of the scandal of Alwyn's neglect. But......

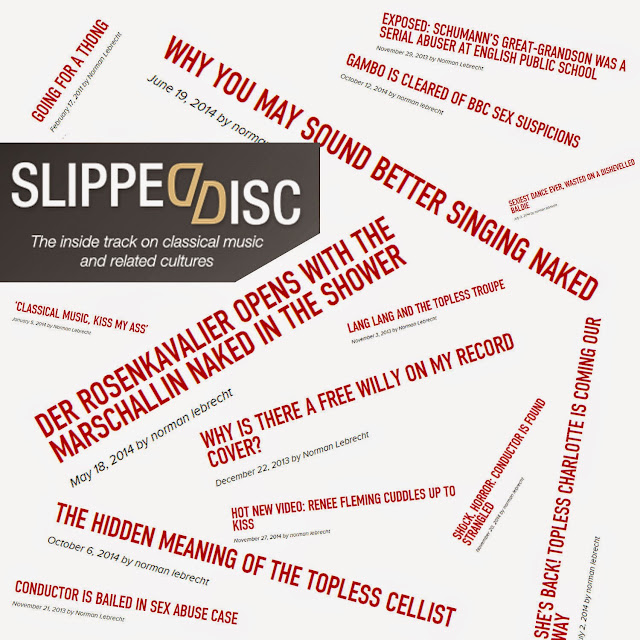

The screenshot above was taken on the day of the concert. The grey seats were sold, the coloured seats were unsold. Which means Snape Maltings was two-thirds empty for the concert. Many explanations can be proposed for the poor attendance. As I have acknowledged, Alwyn's Fourth Symphony is little-know. But it was coupled with three crowd-pleasing works including the Elgar Concerto which is ranked at seventeen on the Richter scale of musical popularity, the 2017 Classic FM Hall of Fame. Another possible explanation is that the orchestra, conductor and soloist do not have the dubious distinction of being classical celebrities. Undoubtedly the hall would have sold out if Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra had essayed Alwyn's symphony. But those who study form will know that John Gibbons' interpretations of Malcolm Arnold's music have been acclaimed, and further afield his recording of a new 'completion' of Bruckner's Ninth Symphony for the Danish Danacord label has been warmly received by critics. It can also be argued that filling the hall for a mid-week October evening concert on the Suffolk coast is a big ask; but the tickets were commendably low-priced for such a meaty programme. So despite these explanations I was still left pondering as to why an excellent and commendably balanced concert resulted in one of the emptiest halls I have seen in more than fifty years of concert going.

We should be very thankful that the William Alwyn Foundation and Snape Maltings are prepared to promote concerts that dare to omit a Mahler symphony, and they most definitely should not be blamed for the sparse audience last night. Empty seats at a concert of William Alwyn's music may not raise many eyebrows; but those at the recent Salonen Stravinsky/Ravel/John Adams BBC Prom and - even more surprisingly - at the Barenboim Birtwitle/Elgar BBC Proms should. (The many defenders of the classical status quo will cite encouraging overall attendance figures for the BBC Proms. But the Proms enjoy 'free' high profile advertising on BBC Radio and TV which would cost in excess of £1 million if bought at market rates. Attendances at celebrity concerts are also showing more resilience due to classical music's shift to a rock music business model; this resilience is however at the expense of non-celebrity events such as last night's Snape concert).

My thesis is that the empty seats are an indication of a serious malaise that is not only beyond the control of those involved in last night's concert, but is beyond the control of the entire classical music industry. A recent Overgrown Path post highlighted the threat that disruptive technologies pose to classical music. Uber and Airbnb are examples of disruptive technologies that have radically changed the business models of other industries, arguably for the worse. Online entertainment and free content are disruptive technologies that are undermining classical music's traditional business model. Whether we like it or not we are seeing a structural shift in consumer tastes, habits and spending patterns driven by free and very low-cost online content.

The appeal and power of online entertainers is reflected in their earning power. Topping the YouTube earnings chart in 2016 was PewDiePie - sample here if you must - with earnings of $15.5 million; while a star such as Colleen Balinger - who impersonates a tone-deaf singer - lingering as low as number ten in the YouTube ratings earns a paltry $5 million. These earnings are simply a reflection of the popularity of these stars: single YouTube videos from PewDiePie generate up to 20 million views. Arguments about the artistic merit of PewDiePie are redundant. Whether we like it or not he and his emerging form of entertainment are attracting huge online audiences and that will not change. The Internet is now the primary source of entertainment - particularly for classical music's prized young target audience - and the antics of PewDiePie and his peers come at no cost to them. Streaming services, which typically come at an unrealistically low cost, are another major driver in this structural shift in the way entertainment is consumed.

The willingness of the classical music industry from the Berlin Philharmonic and London Symphony Orchestra downwards to jump on the free content bandwagon has always lacked any convincing rationale. But there is hard evidence of the damage being wrought by free content. Jonathan Taplin's 'must read' Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Have Cornered Culture and What It Means For All Of Us spells out how Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in real terms the average yearly entertainment spend on movie tickets, event admissions including live music, and other entertainment in the U.S. for the sub-25 demographic fell from $393 in 1998 to $249 in 2012. That 37% fall in expenditure is accounted for by the increased availability of free content on YouTube, pirate sites and social media, coupled with the increasing availability low-priced legal streaming services, and there is no reason to believe that the trend is not repeated in other demographic groups and other countries. The much-lamented ageing of the classical audience - sadly the average age at last night's Snape concert was very high - is almost certainly because the erosion of entertainment expenditure started with young early-adopters of digital platforms, and its full impact has not yet reached older demographics.

The LSO conducted by Simon Rattle performing Berlioz's Damnation Of Faust - all 2 hours 44 minutes of it - can be watched free on YouTube. I wonder how many music lovers stayed at home to watch this instead of supporting the Alwyn concert? Of course it is overly simplistic to blame the last night's poor attendance at Snape solely on a shift to online entertainment. But when a butterfly flaps its wings over the Suffolk coast storm clouds gather over Berlin and London. Classical music's heartland is facing a perfect storm caused by the convergence of two off-shore hurricanes: these are the shifts in consumer tastes and the rapidly increasing availability of free online content - four hundred hours of new YouTube content are uploaded every minute. Classical music must adapt to these changes if it wants a healthy future. But key to this adaption is an acceptance that the gross oversupply of classical music, both live and streamed, must be tackled. At the core of the artform's current problems is the mistaken belief that artistic merit and popularity are one and the same thing. This has led to the destructive chasing of audience via dumbing down and the misguided provision of free content, the latter being the artistic equivalent of giving the crown jewels away. Free content on YouTube and Facebook not only threatens live music attendances, but it also supports cynical tax evasion practices that remove money from public funding channels.

Sterling and much-needed work is being done to tackle problems such as gender and ethnic inequality in classical music. But there is currently absolute denial of the equally serious problem of oversupply, because trade bodies such as the Association of British Orchestras have a vested interest in maintaining or even increasing supply chain capacity. Until the problem of oversupply is tackled, and until faddish and damaging solutions such as live Facebook streams are abandoned things will not improve. The sources of oversupply are self-evident: they are not the rare performances of William Alwyn's symphonies, but the New York Philharmonic's hundred-and-nineteenth outing for Mahler’s Fifth Symphony highlighted by Alex Ross in the current New Yorker.

Classical music has become obese and urgently needs to slim by reducing supply in response to changing market conditions and reduced demand. Live music outside the celebrity arena also desperately needs supporting. The celebration of William Alwyn's music continues at Snape until October 15th. If you are in the area please support it. Because if you don't the William Alwyn Festival may have to reinvent itself as a YouTube channel.

Our tickets for last night's Snape concert were purchased at the box office. Any copyrighted material is included as "fair use" for critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Also on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments

https://medium.com/cuepoint/the-devaluation-of-music-it-s-worse-than-you-think-f4cf5f26a888

I wondered if the Nashville writer's contention of Anti- intellectualism has been addressed by you, other than by the occasional glancing, acerbic aside on "omission of a Mahler symphony"?

Wish I could make it to Snape this weekend!

Tom