Music and politics

A distinguished American lawyer recently said to me that a fine performance of a Beethoven Symphony could move him far more deeply than any kind of preaching. Although that may not be everybody's experience (much as wish it were, I rather fancy that it is not), I feel that there is a good deal in the belief that the spiritual power of great music can sometimes go beyond the meaning of words. And I have often wondered how music can best be used to heal some of the wounds of a divided world by that very spiritual power. (My eminent colleague Dr Koussevitzky no doubt had similar feelings about this matter, for not so very long ago he submitted that it would be a good idea if all members of international conferences were forced to listen to a symphony concert or opera for a couple of hours every evening! Perhaps however, this might be seen as a form of 'punishment' or 'medicine' to be inflicted on such statesmen.)

A distinguished American lawyer recently said to me that a fine performance of a Beethoven Symphony could move him far more deeply than any kind of preaching. Although that may not be everybody's experience (much as wish it were, I rather fancy that it is not), I feel that there is a good deal in the belief that the spiritual power of great music can sometimes go beyond the meaning of words. And I have often wondered how music can best be used to heal some of the wounds of a divided world by that very spiritual power. (My eminent colleague Dr Koussevitzky no doubt had similar feelings about this matter, for not so very long ago he submitted that it would be a good idea if all members of international conferences were forced to listen to a symphony concert or opera for a couple of hours every evening! Perhaps however, this might be seen as a form of 'punishment' or 'medicine' to be inflicted on such statesmen.)Seriously speaking, I do think that music opens up immense spiritual and psychological resources in the task of lessening some of the misunderstandings which result in political conflicts and their attendant social disasters.

Once when I was Director of Music at the British Broadcasting Corporation, a distinguished ex-soldier who had taken control of the programme output of the BBC said to me: 'I left the Army and came to the BBC, simply because I felt nthat if anything can prevent another war broadcasting will do it. This I feel will be the first duty of broadcasting. Now, how are your crotchets and quavers going to help s prevent a war?'

That question has haunted me ever since. And now I am more convinced than ever that interpreters of the great tone-poets also have some duty in working for that kind of understanding and spiritual harmony, without which civilisation cannot go forward.

How, indeed, can the language of music help? Being abstract and universal, this language is already a unifying force among the peoples of the world. The interpretative powers of executants, and the guidance and clarification which musicologists and historians are able to offer, seem to be sufficient in spreading its message. Nevertheless, there is something which nations and organisations can do to enhance its function, especially in these times of conflicting ideologies and power politics.

I feel there is insufficient personal contact between musicians, whether singers, pianists, conductors, or composers. Not even composers, given as they are to battling with creative problems in a seemingly abstract world of sound, can afford to do without that kind of liaison. Understanding will always remain a powerful weapon in solving complicated world problems, and governments must learn to depend more on art in gathering together the threads of such understanding. They would do well, therefore, if they systematically subsidised the visits of certain orchestras and composers to other countries.

I feel there is insufficient personal contact between musicians, whether singers, pianists, conductors, or composers. Not even composers, given as they are to battling with creative problems in a seemingly abstract world of sound, can afford to do without that kind of liaison. Understanding will always remain a powerful weapon in solving complicated world problems, and governments must learn to depend more on art in gathering together the threads of such understanding. They would do well, therefore, if they systematically subsidised the visits of certain orchestras and composers to other countries.From my own experience I have learnt to appreciate the usefulness of personal contact. During my work for the British Council I have always felt that personal contacts with fellow musicians in other countries have not only confirmed but actually widened the universality of music in its power to transcend frontiers and misunderstanding. There was a strong feeling that something really concrete had been achieved when, for instance, the BBC Symphony Orchestra was allowed to entertain the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras. When will we be able to welcome someone like Dmitri Shostakovich to this country and when will someone like our own Benjamin Britten be able to return such a compliment in Soviet Russia?

All misunderstandings, political ones included, are evil in essence. We need the help of the language of music to make them less formidable.

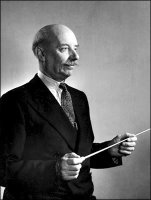

Sir Adrian Boult (photo above) wrote this essay, which he titled Music and politics, for the magazine European Affairs in October 1949, and it is reproduced in Boult on Music, Toccata Press 1983.

* My header photo shows the scene in 1989 as Leonard Bernstein conducted the historic "Berlin Celebration Concerts" featuring Beethoven's Ninth Symphony played on both sides of the Berlin Wall, as it was being dismantled. The concerts were an unprecedented gestures of cooperation, the musicians representing the former East Germany, West Germany and the four powers that had partitioned Berlin after World War II. The concert was put together by Justus Franz, who was then artistic advisor to the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Famously the text of the Ode to Joy was changed, where Schiller had written Freude (Joy), Bernstein and Franz substituted Freiheit (Freedom). Bernstein, who was never one for understatements, said: "I am sure we have Beethoven's blessing".

Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Report broken links, missing images and other errors to - overgrownpath at hotmail dot co dot uk

If you enjoyed this post take An Overgrown Path to The Berlin Philharmonic's darkest hour

Comments

I agree on the moving deeply, but what does it move people to?

A thought rather than an assertion

Gert