Masses of early music on iPods

'Mass settings or collections of motets were never intended to be heard in unbroken sequences as they often are today, and once one has started performing sacred liturgical music to a concert or record-buying audience, and in a context so remote from the composer's intentions, arguments about what is or is not appropriate or authentic in terms of presentation become fairly pointless. It is wonderful that people still love the music, and if a general audience today that might be unlikely to listen to a whole Palestrina Mass might still enjoy one of his beautiful Agnus Dei settings, or a few 'sampled' gems from one of Byrd's large motet collections on their iPods, who should complain?'

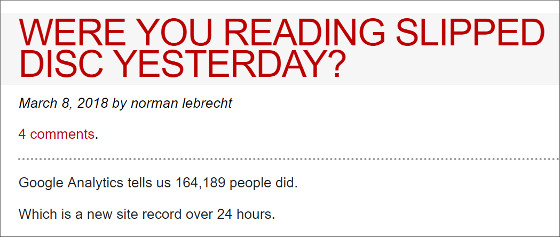

Those are the words of the founder and director of the William Byrd Choir Gavin Turner. In August last year I wrote a very complimentary review of Hyperion's re-release of Masterpeices of Portugese Polyphony, but also commented: "The only quibble (and it is just a quibble on a super-budget priced CD) is the absence of any information on the sleeve (or the Hyperion web site) about the singers- the William Byrd Choir, or their director Gavin Turner. They have one other recording listed on the Hyperion site (Byrd: Benedicta et vererabilis & Alleluia) but I can provide no other information." Hyperion never had the courtesy to reply to my request for information (too busy with the fall-out from the Sawkins appeal result?), but Gavin Turner did. A friend of his read my article, and I recently received a fascinating and wide-ranging update from Gavin which is published for the first time below. This gives both a valuable insight into the fragile existence of specialist ensembles like the William Byrd Choir, and also some interesting thoughts on leveraging iPod and other technologies to widen the audience for Renaissance music. Here is Gavin fascinating account of the choir's history.

'I ran a student early music ensemble, sang in the university chamber choir and at St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral when a student in Edinburgh in the Sixties. I was an alto lay-clerk at Gloucester Cathedral for 18 months in 1966/67, before becoming a civilservant in London. I also worked as a music journalist for the now defunct Music and Musicians and Records and Recording magazines. In London I sang with John Hoban's Scuola di Chiesa and for some years deputised in various professional church choirs in London. In 1984 I was transferred to Edinburgh to run HMSO's Scottish Office (photo above), and lost touch with the professional music scene in London. After working in Norwich and then in London again in the Nineties, I finally retired to live in North Norfolk.

The William Byrd Choir was founded in 1973, and always specialised exclusively in the church music of the late Renaissance (Byrd especially, Gibbons, Weelkes and co, Palestrina, Victoria, Lassus, etc). Our first appearance was at a lunch-hour concert at St Andrew's Holborn. It was attended by the distinguished BBC producer Basil Lam, and we started doing Radio 3 broadcasts almost immediately, which continued throughout the Seventies, mainly with the early music producer Hugh Keyte. However in the early Eighties, partly to do with restraints imposed by Equity, partly because of BBC cutbacks, the BBC virtually stopped making its own recordings with the various professional early music choirs.

We did our first Queen Elizabeth hall concert in 1975, and continued giving regular concerts there and in other London concert halls (the Purcell Room, St John's Smith Square, and the Wigmore Hall) in the late Seventies and early Eighties. We did English festivals like Bath and Camden, and we toured abroad to Spain and Portugal, and to Italy several times.

In 1980 we went to Rome with a BBC production team and made the first recordings by an outside choir ever to record in the Sistine Chapel. (Photo at head of article is the choir recording in the Sistine Chapel). For various classically Italian reasons, the recording sessions were rather fraught and we were not very pleased with the results.

Our main recording was a curious Soriano double choir re-working of Palestrina's celebrated Papae Marcelli Mass which we sang with male voices only. It was originally broadcast in Hugh Keyte's Octave of the Nativity series on BBC Radio 3. The Soriano Mass was a particularly odd choice by the producer, because singing as we were, all cramped together in the tiny choir gallery set high up into one of the side walls of the Chapel, no antiphonal or spatial effects made any impact whatsoever. We also had no sense at all of the effect our sound was having in the vast space below. The acoustic picked up the soprano falsettists and blotted out all the lower voices. One would need to work for some time in the Sistine Chapel to get to grips with that alarmingly resonant acoustic. Indeed, it is now thought that in Palestrina's day, because of the acoustical problems, they probably used only one voice to a part, which would have produced less volume to be magnified by the acoustic and more clarity for the individual vocal lines

From the floor of the Chapel we also recorded a highly embellished version of the Palestrina Stabat Mater and the Allegri Miserere. In spite of tuning and balance problems, the BBC insisted on producing a commercial recording of the Mass for St Sylvester (BBC Artium REGL 572), because they said it was such an 'historic' recording.

In 1978 we made our own recording in St Jude's on the Hill in Hampstead of music by Byrd with Hugh Keyte as producer. We sold the tapes to Philips and they issued it as a stereo LP (9502 030) in 1979. The two Hyperion recordings were Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony (1986), and Marian Masses from Byrd's Gradualia (1990). They were made after the Choir had stopped working regularly as a recital/broadcast choir. These have recently be re-released as CDs on the Helios budget label. Both had good reviews. They have sold around 15,000 and 10,000 respectively, which is apparently fairly impressive for early music recordings.

The Choir worked with a number of distinguished early music editors.Bruno Turner produced a sequence for us called Iberian Requiem, which was broadcast on Radio 3, given at a QEH concert, toured to Portugal and (without the Spanish element) was made into the Hyperion recording. The original sequence included the now famous Alonso Lobo Versa est in luctum of which I believe we gave the first modern performance, though it has since been much recorded by other choirs. Sally Dunkley produced a number of original editions of English and Portuguese music for our broadcasts, recordings and concerts, and Philip Brett advised on the Byrd Gradualia recording.

One of the main reasons why I gave up while the choir was still very successful, and apart from the difficulty of organising London concerts while I was living in Edinburgh, was simply the cost of it all. I could not afford to pay a manager, so I did everything (booking musicians and venues, organising publicity and PR, chasing potential sponsors and the London Orchestral Concert Board, negotiating with foreign festivals, booking flights and hotels, paying BBC repeat fees to all the singers, doing Choir accounts for the Charity Commission, etc) while doing my normal job as well. I used to arrive on the podium at QEH barely having had time to think about the actual music. I remember a musical lodger of mine saying: 'I bet John Eliot Gardiner isn't sitting at home after midnight the day before a concert stapling programmes together!' Over a period of about six years in the late seventies, I spent around £25,000 ($ US 44,000) of my own money promoting London concerts - which was quite a large sum in those days. It is easy to see now that I might have been better off to have done what certain other groups who started about the same time did, to spend money on setting up a record label which would have produced some income, rather than frittering it away on self-promoted concerts which always lost money, however successful at the box office and critically. Having made a good recording of Byrd in 1978, perhaps we should have made our own LP rather than selling the tapes to Philips; but at the time it seemed less hassle, and I thought it would get more high profile sales - which it did.

In a way I am sorry I did not persist. I was interested in slightly later English repertoire than that which the Clerks of Oxenford, The Tallis Scholars and the Sixteen made very popular, and it is only relatively recently that people have really got stuck into the Byrd repertoire.

The revival of the Choir as a recording ensemble is still under consideration. I am quite interested in the recording possibilities that iPod technology has opened up for much of this repertoire. Masses aside, much of the music that we used to perform is in fairly short slugs - the same length as pop tracks. Now that people can 'sample' their Keane or Franz Ferdinand, they are also starting to sample classical tracks for their iPods too, and Renaissance polyphony is particularly suitable for this. I suspect fewer and fewer people, apart from the geeks, will want to sit down and listen to 80 minutes of two or three minute tracks (cf our Hyperion Byrd CD which I must confess that even I find unlistenable-to as a whole). Mass settings or collections of motets were never intended to be heard in unbroken sequences as they often are today, and once one has started performing sacred liturgical music to a concert or record-buying audience, and in a context so remote from the composer's intentions, arguments about what is or is not appropriate or authentic in terms of presentation become fairly pointless. It is wonderful that people still love the music, and if a general audience today that might be unlikely to listen to a whole Palestrina Mass might still enjoy one of his beautiful Agnus Dei settings, or a few 'sampled' gems from one of Byrd's large motet collections, who should complain? However, launching into the iPod market successfully would now require quite a lot of money too.'

(c) On An Overgrown Path & Gavin Turner 2006. Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Report broken links, missing images and errors to - overgrownpath at hotmail dot co dot uk

Comments

Signum Classics have just released a CD single of the King's Singers (muti-tracked to 40 voices) performing Tallis' Spem in Alium.

Follow this link for details.

Learn to use an iPod at Selfridges - for just £65

Press Association

Monday January 16, 2006

Help will soon be at hand for technophobes who don't have a clue how to use their iPods - but at a price.

One-to-one "iPod survival" tutorials costing £65 for 40 minutes are to be offered at Selfridges department store in London. Subjects covered will include using iTunes, installing videos, creating playlists and downloading podcasts.

Kristina Rate of Selfridges said staff giving the one-to-one tutorials would be iPod enthusiasts. "Our guys basically know everything about it by really being interested. There isn't such a thing as an iPod school or an MP3 player course," she said.

From today's Guardian

Have to agree with him about the Palestrina CD he put out. I don't have it, but heard it in a friend's room at University a good few years ago. I think the excuse in the liner notes for the um ... 'richness' of the sound was that they didn't have the Chapel filled with weightily-vested clerics!