Research proves audiences become what they listen to

During yesterday's Aldeburgh Festival performance of Jonathan Harvey's Fourth Quartet by the Arditti Quartet truly extraordinary things happened. Jonathan Harvey's music is rich in influences, among them Hinduism and its reformed cousin Buddhism. Yesterday his Fourth Quartet transformed Aldeburgh Church into what in those Eastern traditions is known as a tirth, a transcedental location where one can "cross over", and that transformation triggered in me one of those rare experiences of being transported by music to another and better world. That elusive experience of momentarily "crossing over" is, for me, the raison d'être of music, and unlocking the secret of how it is achieved also unlocks the secret of how classical music can reach new audiences. So today's post explores the path which took me briefly to that different and better world, and it is a path that has led me to the conclusion that we become what we listen to.

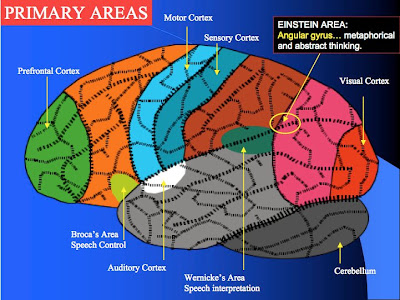

When I first wrote about Jonathan Harvey's String Quartets in 2009 I said "I am not ashamed to admit that some of his music comes from a point that I haven't yet reached". Since then I have been exploring how we can extend our mental reach, and that has led to recent research into neuroplasticity. This is the brain's newly-discovered ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections, and the discovery of neuroplasticity indicates that classical music is wrong in the way it is trying to reach new audiences. Until recently it was thought that the adult brain is an unchanging and unchangeable organ, and that human behaviour and responses are hardwired genetically into it in the same way that computer operations are etched into a microchip. But recent medical research has shown that the adult brain is, to quote the pioneering researcher Michael Merzenich, "massively plastic". Our brain cells are continually breaking old connections and making new ones, with the result that new nerve cells are always being created. As the leading professor of neuroscience James Olds explains, "the brain has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly, altering the way it functions". One celebrated study by Edward Taub showed that playing the violin resulted in significant physical changes in the sensory cortex of the brain. Another study of London taxi drivers showed that purely mental activity can also rewire the brain, while studies at Harvard and the University of Wisconsin have shown that meditation beneficially increases cortical thickness. As the influential technology commentator Nichola Carr explains, "we become, neurologically, what we think".

If medical research proves that meditation can rewire the brain, it is not unreasonable to hypothesise that repeated exposure to music that "comes from a point that I haven't yet reached" can trigger the same changes. If my hypothesis is true, and I genuinely believe it is, there are profound implications for classical music: because, neurologically, we become what we listen to.

It is beyond doubt that classical music must develop its own form of plasticity in order to adapt to wide-ranging cultural and technical changes. But the favoured method of adaptation is based on the outmoded theory that, because listeners are unchanging and unchangeable, audiences should only listen to what they have become conditioned to. This theory has found expression in the dumbing-down approach, and this has led classical music down several fashionable cul-de-sacs, most notably those of reinventing art as entertainment and proscribing any music that is remotely challenging. This approach is doubly dangerous, because not only does it ignore the ability of listener's to adapt to the unfamiliar, but it also ignores recent research that has identified a reverse form of neuroplasticity which results in ossification. This suggests that if you keep feeding audiences single movements of symphonies à la BBC Radio 3 breakfast programmes, they will eventually only be able to digest single movements of symphonies.

By contrast research into neuroplasticity supports the dumbing-up approach. Because audiences become what they listen to, they will become progressively more receptive to challenging repertoire if exposed to it in the right circumstances. Dumbing-up means offering audiences a varied repertoire that mixes the accessible with a changing and challenging diet of the unfamiliar. The problem is, however, one of time scale. Dumbing-down is a short-term solution which panders to today's demand for instant gratification. But dumbing-up is a long-term solution that requires courage and long-term commitment from orchestras, broadcasters and record companies, and such courage and commitment is very rare today. However the clinching argument is that, as has been explained here before, there is no empirical evidence that the short-term dumbing-down solution of giving the audience what they have become conditioned to actually works.

This post started with my experiences at a recent concert. To conclude I want to look back to one of my earliest experiences in the concert hall, which was being taken by my far-sighted parents to a concert in an enterprising London Philharmonic Orchestra 'classics for industry' series in the early 1960s. The venue was the Royal Albert Hall, the conductor was a young Bernard Haitink, and the programme juxtaposed Beethoven's popular Emperor Concerto with Berg's forbidding Three Pieces for Orchestra op 6. At some point in those twenty-one minutes of Berg some old connections in my brain broke and new nerve cells began forming. Those neurological changes started me on the long and infinitely rewarding path from classical neophyte listening in puzzlement to Berg, to classical adept relishing Jonathan Harvey's Fourth Quartet. If you are one of the many readers who has benefited from the musical discoveries I have shared On An Overgrown Path, you are also a beneficiary of neuroplasticity. If it worked for you and me, surely it can work for today's new audiences?

* More on how audiences become what they listen to here.

** My 2010 radio interview with Jonathan Harvey, which includes his memories of Benjamin Britten, is transcribed here.

*** Footer image shows the highly recommended Arditti Quartet's recording of Jonathan Harvey's Quartets and String Trio.

**** Sources include The Shallows: How the Internet is Changing the Way We Think, Read and Remember by Nicholas Carr and The Autobiography of a Sahu by Rampuri.

Our Aldeburgh Festival tickets were bought at the box office. Header image credit Wikipedia. Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Also on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments

I agree with you that the newly discovered plasticity of the brain is one of the most promising things to come out of the new neuroscience. We can literally change how we think and how we process sensory input. Plato's talking about how some modes of

music are better for us to listen to than others seems less arbitrarily judgmental seen in this light.

What this really makes me think of is the term "flow", the term Csikszentmihalyi came up with to describe that "crossing over" that can happen when performing music and the music seems to be happening of it's own.

It would be interesting to know how the performers felt about that particular performance. From what I can tell anecdotally, a performance that's a flow experience for the performers is more likely to trigger "crossing over" in the audience, but that it's not necessary. It's also possible that someone sitting right next to you was bored to tears by the same performance.

First, you say "Hinduism and its reformed cousin Buddhism." I'd suggest you read at least a Wikipedia page to find out a bit more about Buddhism; it's neither a cousin of Hinduism, nor a "reformed" version of it. But that's not the crux of your post.

You then say:

"This is the brain's newly-discovered ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections, and the discovery of neuroplasticity indicates that classical music is wrong in the way it is trying to reach new audiences."

Well, first, neuroplasticity is not "newly-discovered;" it's just that it's been in the spotlight recently, because a number of vulgarized books have been published about it. It's been fairly well-known and accepted for a couple of decades now. Second, this has absolutely nothing to do with "trying to reach new audiences." You seem to think that somehow listeners need to be brainwashed into liking classical music; I know, that's a bit harsh, but that's what comes across in this statement.

Next:

"It is beyond doubt that classical music must develop its own form of plasticity in order to adapt to wide-ranging cultural and technical changes."

I don't know what you mean by classical music developing "its own from of plasticity." This sounds like post-modern drivel, and means nothing. Honestly.

And this:

"By contrast research into neuroplasticity supports the dumbing-up approach. Because audiences become what they listen to, they will become progressively more receptive to challenging repertoire if exposed to it in the right circumstances. Dumbing-up means offering audiences a varied repertoire that mixes the accessible with a changing and challenging diet of the unfamiliar."

I think this has nothing to do with "neuroplasticity;" you're falling into the now-common trap of neuro-whatever to define something. It's more about a musical vocabulary that people need to learn. When you're used to diatonic scales, chromaticism is dissonant; you need to learn the vocabulary, or the phonemes, if you prefer, of this new type of sound. The more you're exposed to these scales, intervals and chords, the less they shock you.

Finally, regarding the main crux of your post, where you say:

"Yesterday his Fourth Quartet transformed Aldeburgh Church into what in those Eastern traditions is known as a tirth, a transcedental location where one can "cross over", and that transformation triggered in me one of those rare experiences of being transported by music to another and better world."

This is indeed interesting, but has nothing at all to do with neuroplasticity. This is an experience that people have at different times, and it can be caused by music, by smells or tastes (cf Proust's madeleine), or other stimuli. In zen, this is called a kensho experience, and when one has them, they are very nice, but one doesn't strive to have them; they just happen when they do.

I describe a similar experience on one of my websites:

http://www.readingemerson.com/2011/07/10/emerson-and-zen-buddhism/

As to becoming what one listens to, there is certainly evidence that different types of music have effects on the brain. The problem is that no one has much of an idea what types of music do what, or to whom, or how. The bit about playing Mozart to babies to make them smarter has been disproven.

And, as someone who has meditated for a couple of decades, and who has read a lot of the research, I see little link between meditation's effects and that of music. While certain types of music can certainly relax people - this is well-known and has been tested frequently - others can have other effects. If, say, a Mozart piano concerto relaxes, and an atonal string quartet enervates, then it's not "classical music" as such, but specific types of music that may have effects.

In Peaks and Lamas page 301 Marco Pallis explains:

"Similar considerations would have applied in India during the centuries when Hinduism and Buddhism coexisted there as separate currents of tradition: both continued to belong to the same civilization, the form of which had been laid down, under purely Hindu inspiration, at a time long anterior to the specific formulation of the Buddhist teachings. In an case, both in virtue of its origin and by the nature of its thought, Buddhism remains an Indian doctrine, having derived most of its basic conceptions, if not all, from the common root-stock of the Hindu metaphysic".

Perhaps it is not me that is muddled.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The Harvey was absolutely mindblowing, and I would say I experienced the same "tirth" as you did in your recent post. The music was a hive of richness. It was both simple to apprehend on the surface (when you sense the music is "breathing" this structure allows you a cradle in which to place all the sounds - arguably the same soundworld housed in a more traditional structure would be harder to follow) and yet ludicrously and ecstatically complex when zoomed in on (like the structures of life itself). The image I thought of was a bucolic mountain stream: its trickling is musical to the ear, the complex play of sunlight on the water is beautiful to the eye - and yet the patterns which interweave to create these overall effects are magically intricate.

It was also touching to note that, as a UK premiere, we were some of the first people in the world to hear this music. It's art at the cutting edge, exploring paths that no one else has trodden, and may never after, typical of a late style/late flowering of an artist: a sudden flight to convey ideas which have been earned through a lifetime and must be released before they are gone, a rush of energy like a dying star. This soundworld of the composer had been imagined in the brain of an artist, trapped in the pages of a score, and was now resounding in space - bouncing around the hall, flowing through new minds. Harvey is now dead and yet the ideas are alive, what was frozen has now thawed (like frozen sea voices in Rabelais Fourth Book of Pantagruel) and I felt that this was true transcendence and immortality, such as it can be experienced in any intellgible and tangible way.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>