From Tchaikovsky to Buddhism and beyond

There is a passage in Tchaikosky's Pathetique Symphony which I find more moving than anything else in the realm of music. Up to that moment, the melodies have been gay and lilting, with only a trace of underlying sadness here and there. Troikas galop through the sparkling snow, diamonds sparkle on the snowy bosoms of beautiful ladies at the ball, whose hands are extended to the lips of men in splendid uniforms. We smell the hot tallow from the chandeliers, the sweetness of the ladies' bouquets and the perfume discreetly sprinkled behind their shell-pink ears. All is love and joy. The composer, Having snatched a kiss from his beloved, rushes home to dream of his good fortune. Bursting with joy, he sees a letter from her on his desk and tears it open. Then:In those distant times when online algorithms did not dictate our tastes in music, Tchaikovsky's Pathetique was one of the works which opened the door to classical music for me; so that tantric appreciation resonates with someone who back in the 1960s realised there was life beyond Sartre and Pink Floyd. The extract comes from The Wheel of Life: The Autobiography of a Western Buddhist by John Blofeld. The book's 1959 publication date explains the somewhat fey language and also the absence of any homoerotic deconstruction of the Pathetique. When John Blofeld graduated from Cambridge in 1933 at the age of twenty he left his native England to begin a lifelong sojourn and study in Asia. In China he studied with numerous Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist masters. As well as becoming one of the leading Western scholars and translators of these religions he was empowered in the tantric Vajrayana School - 'Thunderbolt Vehicle' - of Tibetan Buddhism. John Blofeld's written legacy also includes a translation of the I Ching, two explorations of Tantric philosophy and a co-translation of The Life of Milarepa, and he was one of the first Westerners to publicly explore the practical application of Buddhism in everyday life. John Blofeld died in 1987 in Thailand where he had made his home following the Communist revolution in China.

Boo-hoo boo-hoo! An agonised cry; an anguished sequence of notes which will be woven into the theme of all that follows. It is stark, it is terrible. In real life, countless Russians and not a few Chinese have committed suicide on hearing that awesome symphony. Boo-hoo boo-hoo! I know that cry so well. I knew it before I ever heard the symphony which, owing to my long absences from Europe, did not occur during those Hong Kong years. That terrible sound was the theme underlying not only the symphony but also my life at the time. Despite days or even months of relative tranquility, every now and then a little breath of air would blow down from the distant, as yet unseen, high mountains of Tibet, still fresh with the purity of diamond-sparkling snow; a little shower of the snow itself, magically unmelted by the hot winds of Sangsara and hell, would blow against my cheek. It spoke to me of beauty imperishable which I had glimpsed and lost, which once seen can never be wholly forgotten, nor the anguish of its loss diminished, nor any other beauty take its place.

Tchaikovsky and Buddhism are strange bedfellows; however two auspicious but little-known connections deserve highlighting. One is to a conductor whose interpretation of the Pathetique is arguably one of the most powerful committed to record. Sergei Celibidache was heavily influenced by the pioneering German Buddhist Martin Steinke. The paths of Celibidache and Steinke crossed in Berlin where the conductor studied at the Hochschule für Musik from 1936. Steinke founded a Buddhist sangha in the city with his pupils in 1937. This was banned by the Nazis in 1941 and Steinke was arrested for a short time in by the Gestapo. In 1962 Celibidache wrote an appreciation of Steinke's Lebensgesetz (Law of Love) for the Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung.

There is a second more direct connection that runs from Tchaikovsky through John Blofeld to one of the most important figures in contemporary music and culture. The only book about Zen that John Cage ever acknowledged as influencing his work was Blofeld's translation of the Huang Po Doctrine of Universal Mind. The seminal Lecture on Nothing is thought to have been influenced by Blofeld's Zen scholarship. Blofeld's contention that "the Limitless cannot be caught within the limitations of speech" is reflected in Cage's celebrated lines in the lecture declaring "I have nothing to say/ and I am saying it/ and that is poetry". This leads to the proposition that the Limitless also cannot be caught within the limitation of music, a proposition Cage encapsulated in 4' 33".

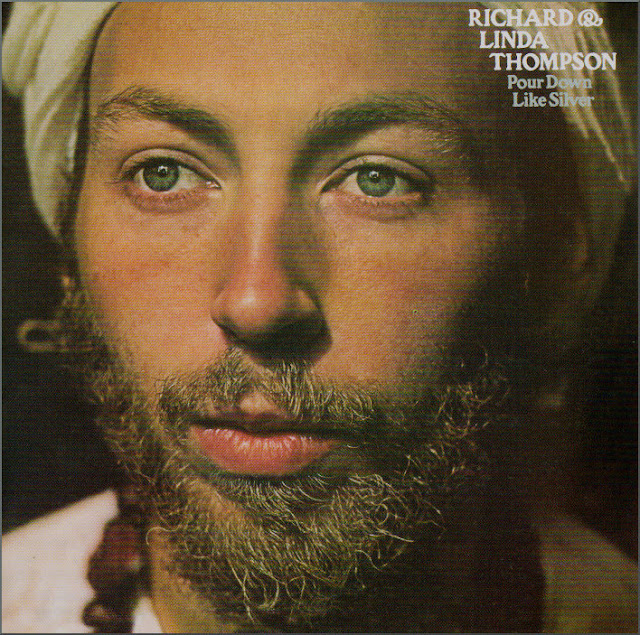

Header image of a Tibetan thangka painting of the Wheel of Life (Bhavachakta) is reproduced from the cover of the Shambhala edition of John Blofeld's spiritual autobiography. Any copyrighted material is included as "fair use" for critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). No review samples used. Also on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments