How enduring is your music?

Scott has left a new comment on your post "Schoenberg and stomach cramps":

On a mildly related topic which would have fit better a few topics back, I've never really come to grips with what "world music" is. Specifically, why are Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan (to mention a personal favourite) often mentioned as world music? Surely they are classical music (or art music) as much as is Schoenberg.Thanks Scott, as ever a perceptive comment. As it's Friday and the sun is shining I am going to freewheel down the path you sent us on with those important words 'more lasting'. Back in 2006, when I was writing on Arvo Pärt's Passio, I quoted Mark Van Doren (from the introduction to Thomas Merton's The Seven Storey Mountain incidentally) as saying:

Sometimes I think that world music is anything that the writer thinks is more lasting than "popular music" but which doesn't fit within the boundaries of western art music or jazz.

'A classic is a book that remains in print'.The test as to whether a piece of music (of any category) remains in performance (live or recorded) is a telling one. 'Enduring music' is not the same as good music. A lot of bad music remains in performance, and, conversely, some very good music is rarely performed. But, as the search for the musical viagra that will rejuvenate the classical format continues, there are some interesting lessons to be learnt from 'enduring music'.

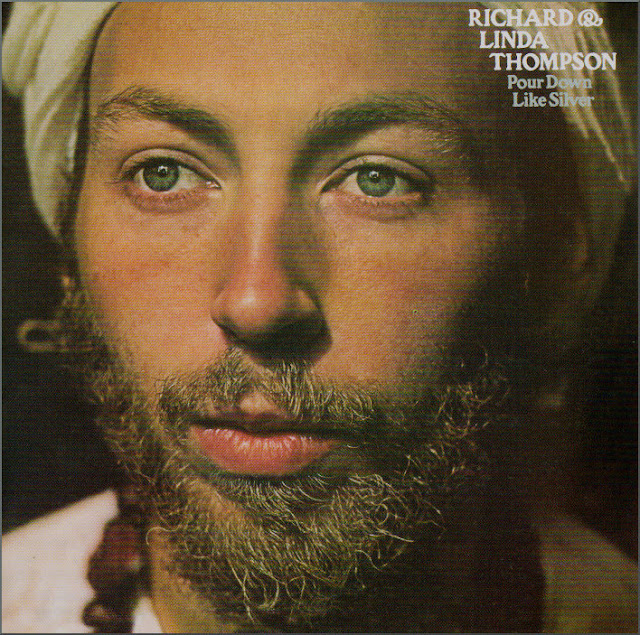

Shakti's 1975 LP, which is seen as a CD re-issue above, links to Scott's comment in three ways. First, Shakti do not fit into any convenient marketing category. Secondly after almost 25 years the album is stil in the catalogue. And thirdly, one of the musicians is a Shankar, albeit no relation to Ravi. Here is the reverse of the album cover:

On the left is the great Tamil violinist Lakshminarayanan Shankar, usually known as L. Shankar, or just plain Shankar. He has worked with many great names including Frank Zappa, Eric Clapton, Charly García, Van Morrison and Yoko Ono. Shankar's extraordinary and essential 1981 CD Who's To Know (subtitled Indian Classical Music) for ECM used a custom made 10-string double violin with an equivalent range of string bass to conventional violin.

While studying at Wesleyan University in 1975 Shankar met John McLaughlin (next to Shankar in photo above) to form the pioneering but short-lived acoustic East-meets-West band Shakti. It would take several posts to do justice to the work of John McLaughlin. He played on four of Miles Davis' albums, was a session musician with the Rolling Stones, and from Shakti McLaughlin went on to form the influential Mahavishnu Orchestra, which deserves at least a post to itself. But it is another John McLaughlin project that I want to follow in this 'enduring music' path.

In 1981, the then director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra Ernest Fleischman asked John McLaughlin to play Rodrigo's Concerto de Aranjuez with the orchestra. The guitarist jokingly agreed on the condition that the orchestra commissioned a concerto from him, and so his concerto for guitar and orchestra 'The Mediterranean' was born. The concerto was premiered in LA in 1984 and was recorded by McLaughlin with the London Symphony Orchestra and Michael Tilson Thomas in 1990 for CBS.

Yes, the concerto is a derivative potpourri linked to Rodrigo's masterpiece by more than the Ernest Fleischman anectdote. But that is not the point of my post. Almost twenty years after its first release John McLaughlin's concerto remains in the catalogue in its original release format. Surely there must be a lesson in that?

Now sample this 'enduring music' for yourself:

More 'enduring music' beyond categorisation here and here.

Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as "fair use", for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s). Report errors to - overgrownpath at hotmail dot co dot uk

Comments

This is from the not always reliable WikiPedia: 'The term "World Music" includes Traditional music (sometimes called folk music or roots music) of any culture that is created and played by indigenous musicians or that are "closely informed or guided by indigenous music of the regions of their origin,"...Most typically, the term world music has now replaced folk music as a shorthand description for the very broad range of recordings of traditional indigenous music and song from around the world.'

Again, this seems to posit some separation of the "West" from the "World," as if "Westerners" were mere interlopers not truly at home anywhere. Thus, the term "indigenous" is itself politically loaded; everyone is "indigenous" to somewhere, but the term is typically used only to refer to non-Westerners, particuarly to favored or fashionable minority or Third World cultures.

Dennis